June 2018

26

Disponible en línea en español.

“Nope. Eels”

“Whatcha doin’ that for?”

“To count ‘em”

He gave us a puzzled look and headed home. His interest was in the run

of herrings which he would use as bait for Striped Bass. The bass follow the

herring upriver.

Yes, we were there to count eels.

The American Eel (Anguilla rostrata) is a diadromous fish, capable of living

in both freshwater and seawater as are striped bass, shad and other herring

species. It’s the alewife that the fisherman was looking for as baitfish. The

difference between these fish and the eel is that they are anadromous,

living their adult lives in saltwater and returning to freshwater only to spawn,

though some say there is a resident population of stripers in the river. The

eel, on the other hand, lives its adult life in freshwater and returns to the sea

to spawn. The adult eels are called brown or yellow eels and when sexually

mature, the age is unclear but it could be eight to fifteen years, they become

silver eels with bulging eyes, darkened backs and a silver sheen to their bellies

and they head downstream.

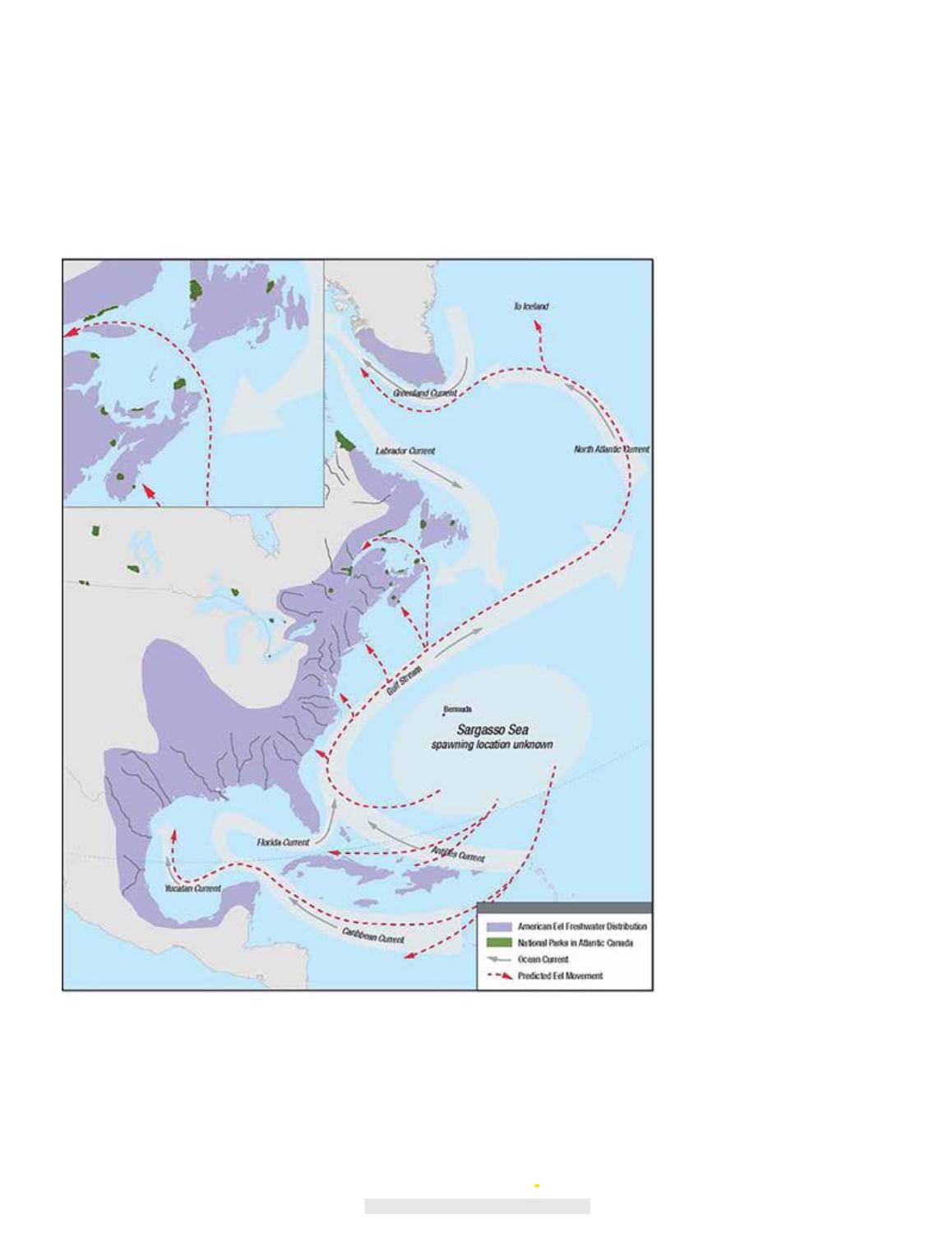

James Prosek in his book “Eels…the world’s most mysterious fish” describes

a working eelman in the Delaware River where, under a new moon and after

a good rain in September, thousands of silver eels begin their migration back

to the sea and his year long work on his stone weir finally pays off on these two

nights. And where are the eels headed? The Sargasso Sea. This is an area in

the Atlantic Ocean between the Gulf Stream that includes the Bermuda Triangle.

Known as the graveyard of lost ships this becalmed sea is covered with a mass

of algae, plastic and other flotsam. It is here,

at depths of 1,300 to 2,300 feet that the

eels, both the American and the European

varieties, spawn. No one knows exactly

where this happens or what triggers it. This

has got to be some wild eel party!

The eel eggs hatch into little leaf-

like transparent water creatures called

leptocephali and after a year of drifting over

the continental shelf they metamorphose

into glass eels which then swim up the

rivers and tributaries. This was what we

were after!

We were working as citizen scientists

through the New York State Department of

Environmental Conservation (DEC) and I

was a volunteer working for NATURE Lab,

a project of the Sanctuary for Independent

Media in Troy, NY. I had heard of the Eel

Project and thought it would be a great way

for the community to learn about the Hudson

River. There is no better classroom than the

great outdoors where learning to become

wet and dirty is an essential part of the

syllabus. I contacted their Citizen Science

group in the Hudson River Estuary Program

and, much to my surprise, they thought that

a week long trial run in the Poestenkill was

a good idea as their most northern sampling

station was in Ravena on the Hannacroix

Creek about a half hour South of Albany.

(They did a trial run in the Wynantskill near

Troy in 2017 with no success.) The Eel

Project began in 2008 with two sites and

now has 14 sites sampling the Hudson

River’s tributaries by over 750 volunteers

and students. Our team included students

from Dan Capuano’s Ecology class at

Hudson Valley Community College, and

students from RPI, Russell Sage and

Skidmore and the three girls from Brittonkill Elementary School that I enlisted by

promising them a life changing experience.

After five days of sampling we caught two pigmented elvers about five inches

long but no glass eels. It was still great fun, putting on waders or hip boots (Molly’s

leaked) and pulling up the net but we really needed to see this near mythical life

form that we were pursuing. So I headed down to Hannacroix Creek where, at low

tide, a half a dozen volunteers from the New Baltimore Conservancy converged.