June 2018

49

boatingonthehudson.com

In the 1920s, when the Phoenicia Fish and Game Association was formed,

followed by the Upper Esopus Rod and Gun Club and Stony Clove Rod and

Gun Club, one of their goals was conservation and restoration of the land. On

Saturday, April 28, from 1 p.m. to 3 p.m., the Phoenicia Library will present

“Sporting Clubs, Saviors of our Catskill Rivers,” by Austin “Mac” Francis, author

of Catskill Rivers and Land of Little Rivers, and Bethia Waterman, co-founder of

the Jerry Bartlett Memorial Angling Collection and administrator of the library’s

Angling Parlor.

While issues such as gun control, the proposed Belleayre Resort project,

and the Ashokan Rail Trail tend to polarize local residents, it’s instructive to be

reminded that people on both sides of these controversies have always had

a love of the land and nature as their primary motivation. In the bylaws of the

Upper Esopus club, one of their purposes was “to promote protection of woods,

waters, and wildlife.” The clubs stocked the woods with game birds and the

streams with fish — over 177,000 fish in 1952 alone — and they fought legal

battles to restore health to the creeks.

In the 1970s, the Phoenicia club joined Catskill Waters, an organization formed

to protest the lack of regulation over the release of water from the Schoharie

Reservoir, through the Shandaken tunnel and into the Esopus Creek, aimed at

maintaining levels in the Ashokan Reservoir, part of New York City’s drinking

water system. New York City Department of Environmental Protection (DEP)

was opening and closing the portal according to the needs of the reservoirs,

creating a rapidly fluctuating environment on the Esopus. Excessive water flow,

which drove the fish into hiding, was followed by complete stoppage of water

that left the fish stranded and dying along the banks.

In 1976, Chuck Schwartz, president of the Phoenicia club, wrote to then state

assemblyman Maurice Hinchey, “I have personally rescued over a hundred wild

fingerling brown and rainbow trout along with various minnows, crawfish and

insect larvae. Other trout and their food were not so fortunate and were left

to dry out and die in the afternoon sun…These trout were wild, and consider

the tremendous amount of insect life which support these trout that were also

destroyed. This food cannot be replaced and it may take years to rebuild.”

After seven years of pressure, theNewYorkState legislature

passed regulations that required DEP to moderate the

release of water through the Shandaken portal, preventing

the intense fluctuations that were so devastating to the fish.

DEP fought the changes, but the legislation spearheaded

by Catskill Waters opened the way for regulation at other

reservoirs in the city water system.

One response to the degradation of the environment in

the 1800s was the purchase of tracts of land by wealthy

individuals. Conflict erupted between landowners and local

people who no longer had access to the land they had

hunted and fished for generations. When gamekeepers

caught poachers on property owned by Clarence Roof

in Neversink — where the Frost Valley YMCA camp is

now located — sympathetic juries refused to convict the

hunters. At least one trial was taken out of town, resulting

in a $70 fine for the poachers. “We think that was the start

of posting property,” said Waterman.

However, the wealthy landowners also formed private

sporting clubs that have contributed to the preservation

of rivers. The Anglers Club of New York, created in 1906,

has a conservation committee. “Most of the private clubs

own water,” said Francis, who described how Ed Van

Put of the New York State Department of Environmental

Conservation (DEC) approached private landowners on

the Lower Beaverkill and other streams. “He persuaded

them to sell access to the water so there could be fishing

on it by anyone, as long as they obeyed rules. All the clubs,

whether public or

private, do feel strongly

about

preserving

the pristineness, the

sanctity, the heritage

they’re part of.”

OnApril 28,Waterman

and Francis will go

deeper into the history

of local public and

private clubs, telling

stories of fishermen

and the activities of the

clubs, especially the

Phoenicia association,

organized by the

Breithaupts, Hillsons,

and Longyears. Their

talk will be recorded

by Silver Hollow Audio

through a grant from

Catskill

Watershed

Corporation (CWC),

which is funded by the

DEP. The grant is the

third in a series that has allowed lectures on the history

of fishing in the Catskills to be recorded and placed, along

with transcripts, on the Angling Parlor website. “It’s an

effective way of archiving local history,” said Waterman.

In last October’s program, Bob Decker described how

his father caught the elusive and wily fish known as Old

Bess in 1955, and Ed Kahil reminisced about growing up

at Rainbow Lodge in its heyday of hosting hunters and

fisherfolk. Fishing legend, author, and talented storyteller

Nick Lyons gave a second presentation in December.

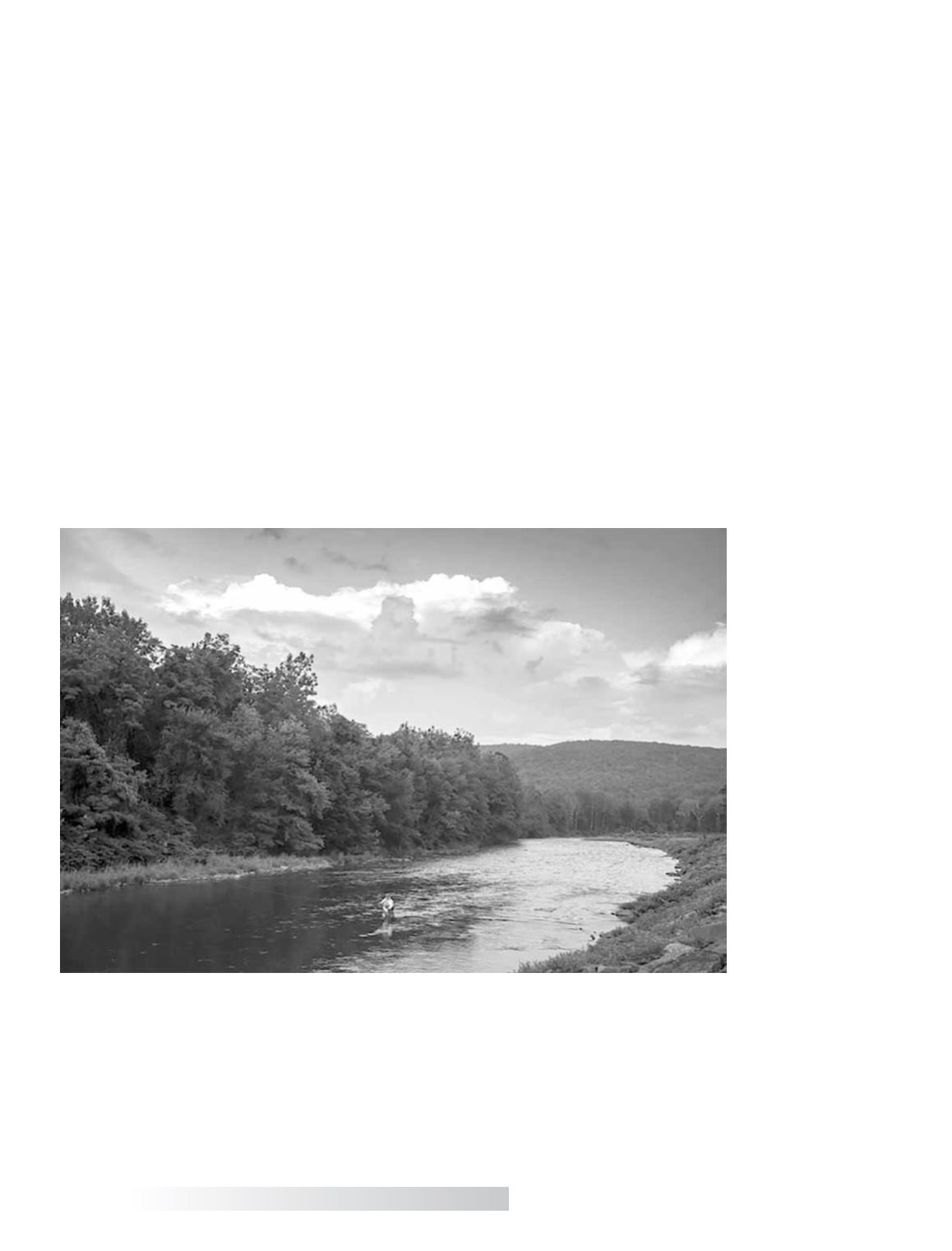

Fly-fishing on the Esopus.

Photo: Dion Ogust